Regarding the Vibrantly Colorful Paintings of Joan Mitchell on a Gray Winter Day

Agnès Madrigal and Jules X

Two writers discover that they both wrote about the same exhibition more than a year ago. Regarding the Paintings pays homage to the Abstract Expressionist artist Joan Mitchell and her ravishing work through two unique perspectives, one critical and one fictional. With galleries at SFMOMA serving as the backdrop for this show and the two writings it inspired, this feature expands what our series Duos can do.

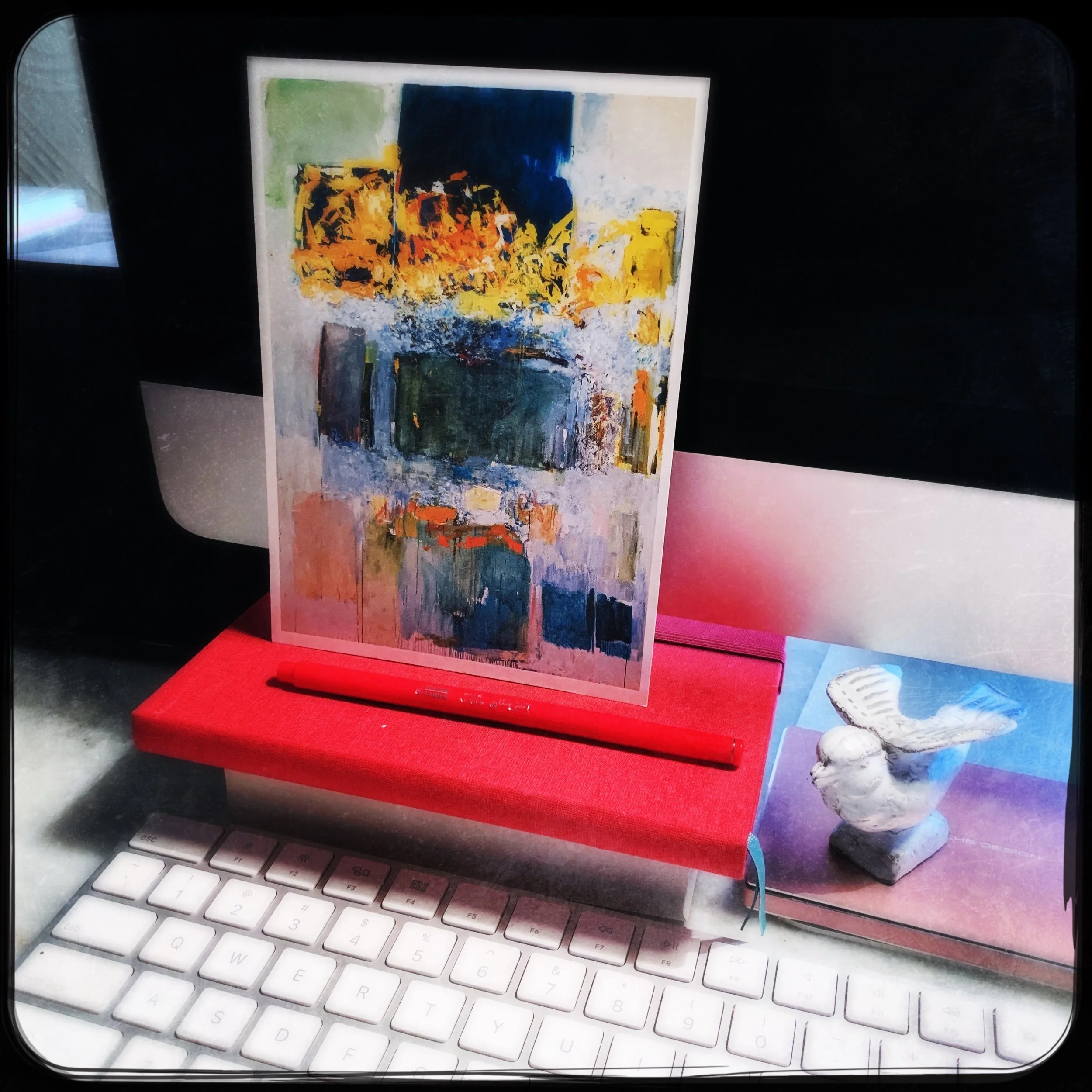

A postcard from the exhibition Joan Mitchell, featuring the painting La Ligne de la Rupture (1970–71) by Joan Mitchell, propped on a desk at Madrigalit. The copyright for the image on the postcard is © Estate of Joan Mitchell. Photograph by Madrigalit

Thoughts on an Exhibition: Joan Mitchell at SFMOMA by Jules X

It is a common gray-white day in San Francisco. The downtown sounds are muted by the pandemic that still drapes its colorless self over just about everything. There’s little traffic now, and none of the prior street performances. Embedded in this cement-laden landscape is the SFMOMA on Third Street. Inside, within the immaculate white galleries, there is a quality that registers differently since the coronavirus—its sleek minimalism is more antiseptic now than it is fashionable. Amid its discomforting sterility, on the fifth floor, in the exhibition galleries, there is, in joyful contrast, a sudden suffusion of brazen color, exalted nature, and contortioning—a word I have possibly made up here—emotion.

Glancing into only the first gallery, one sees immediately the dramatic chaos of paint in works that reverberate, resembling, to my mind, massive, impossible fields, quarries, lakes, flowers, if we can call them flowers at all, for these are not your usual blossoms. These are big-headed awkward flowers. These are paint-smacked oppressive flowers. These are globular and angry devouring flowers, fleurs du mal, should we wish to invoke the words of the poet Charles Baudelaire. But this show is not about flowers, not really. It’s about so much more: rivers, harbors, poems, odes of joy—to offer a start. This is the work of the abstract expressionist artist Joan Mitchell, on regal display, challenging and disputing so much of the rest of our world that surrounds her paintings on this winter day. Her work thwarts now, as it did in her own time, the parameters of the given, the accepted, and even the banal. It rages and it hurls; if it could, it would throw itself against the floors, smearing its pigments everywhere.

“I could certainly never mirror nature. I would more like to paint what it leaves with me.”

—Joan Mitchell

Nature is an easy device, flowers especially. Nature is a simple way to categorize and make sense of these luscious and mucky compositions painted by a woman—what would we otherwise dare say of them? How do we resist the accident of insult, exploitation, belittlement when we speak of a woman’s art? Woman and nature are easily joined, the woman as representation of the earthly. Women are the birthers, the carriers, and men—in opposition to this—the philosophers, the visionaries. Joan Mitchell supports the edifice only in so much as she gives us her titles, like Trees, River, and La Grande Vallée. Who are we—who am I—then to call these works otherwise?

Painters are coy, unforthcoming, I often find, when it comes to the use of words. They don’t require them, so they neither trust them nor take them too seriously. The paint is the language. The stories are already told, on the canvases. Titles are extraneous, though they make for easy points of entry for curators and critics; they make for clearer ways in which to make sense of the glorious and uproarious impastos such as these, these great heaving abstractions that provide no obvious representations. Titles can also deflect, make nice a greater agenda, an anguish, by invoking more serene aspects—the bridges, the jazz, the sunflowers.

“The sheer pulsing color of these works is not drawn simply from nature, but from nature as it is regurgitated, through memory. . . . These strange, saturated hues, often in profound and jagged conflict with one another, speak of this other nature, the one of psychology and of dream, where color is not as we know it in waking life.”

—Jules X, writing about the artist Joan Mitchell

The sheer pulsing color of these works is not drawn simply from nature, but from nature as it is regurgitated, through memory, as the didactics—and even the artist—will try to convince you. These strange, saturated hues, often in profound and jagged conflict with one another, speak of this other nature, the one of psychology and of dream, where color is not as we know it in waking life. Joan Mitchell’s palette is mature, complex, and sometimes even disquieting. We might be tempted to call her renderings primal—a word too quickly associated with women, yet one can fairly easily imagine versions of these glorious messes on the walls of prehistoric caves yet undiscovered. Well, these are my visceral feelings upon seeing these grandiose paintings anyway—all the opulent splatterings, drippings, and smearings—at close range. What qualifies me to share these sentiments? Have I dragged a loaded brush across the surface of a semi-taut canvas myself? Have I felt something of the myriad of feelings that pulsate from these compositions? I am not an art historian. I needed to see these paintings. I needed to feel wholly disabused of any rhetoric and let whatever intimate undoing might transpire. I needed to bear witness to Joan Mitchell’s protest, her sublimation, and her excruciating artistic promulgation.

A lengthier version of this article was published earlier in Jules X’s zine, Julxine.

“Painters” by Agnès Madrigal

Why aren’t more artists painting like that, she wondered, as she exited the exhibition, left the interlocking white galleries with the walls filled with the bright, paint-slathered canvases, some stretched on frames that reached nearly to the ceilings. She entered the wide gleaming hallway of the grand museum, punctuated with the satisfied museum visitors, some in their fashionable clothing, some dressed so brightly as the paintings that fell away behind her as she walked toward the glass café.

She knew something of the question—she had been a painter once—and nothing of the answer. Had she forgotten it? The paintings in the show forced her to remember: the feeling of a brush or a palette knife against an imperfectly sanded surface, the odor of the old-fashioned turpentine, the sound of the brushes swirling in the liquid and knocking against the sides of the jar or tin, and, most of all, the feeling of a color—of just one color—when it was smeared across a plane and to the very edges of that space, to the edges of consciousness, she wrote.

“The paintings in the show forced her to remember: the feeling of a brush or a palette knife against an imperfectly sanded surface, the odor of the old-fashioned turpentine, the sound of the brushes swirling in the liquid and knocking against the sides of the jar or tin, and, most of all, the feeling of a color—of just one color—when it was smeared across a plane and to the very edges of that space.”

—Agnès Madrigal

She ordered a black coffee and a piece of cake with a frosting design like the painting—museums did these things these days, she thought; it was cute, as it not? What was her problem? The cake was dry. She ate it anyway, on the cold rooftop patio that extended from the café and overlooked the downtown. It was so chilly that it was difficult to eat the cake, difficult to hold the pen, difficult to write any of this down. The coffee helped.

Those colors, she wrote, and she stopped there. For what could she say? The colors made no sense. They did not belong together. And, yet, once they were there, combined in the compositions, they made every sense. They did belong together. They began to tell whole new stories, stories she was curious to know, if she could permit herself to find them. She could find them, she wrote, if she painted, if she painted again.

“In the chic little city there was a bit of nature: rounded green hilltops devoid of houses here and there, and, to the west, a great howling sea. Nature had its colors. It had every color.”

—Agnès Madrigal

In the chic little city there was a bit of nature: rounded green hilltops devoid of houses here and there, and, to the west, a great howling sea. Nature had its colors. It had every color. And she knew that these colors were not the same as the limited colors in the magazines, in the street posters, on the computer screens, all of the computer screens . . . The paintings reminded her that there were other colors: shimmering deep blues, queasy-making greens, rapturous red-purples that felt so human somehow, yet she could not explain—

Only that in one of the galleries, in a spackle-like smear of uneasy tan paint, she smelled a lover’s skin. It came to her, the aroma, as memories do, but triggered by nothing more than such color. He was from long ago, they had parted amicably enough at around the same time she gave up painting. Standing in front of the painting, she could be quite sure of him, could feel his breath upon her face, could touch, very gingerly, the delicate skin between her and all of this now, this weeping tenderness.

But that would be a story for another day, a story told not by a painter, but a writer. Her words froze in her notebook, awkwardly rendered across and not between the faint blue lines, where they would stay, fixated until her thoughts could change.